Archipeligo of Archives

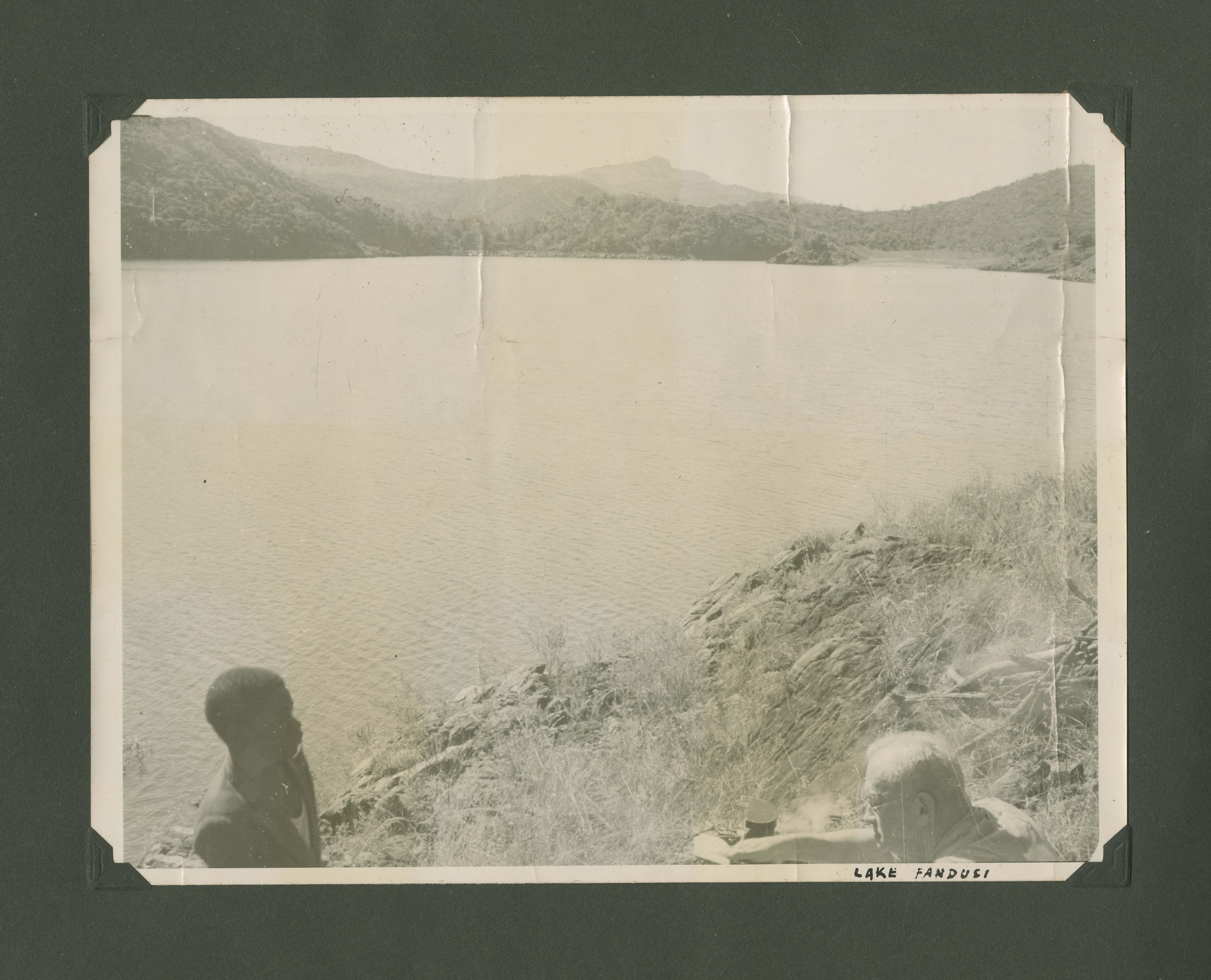

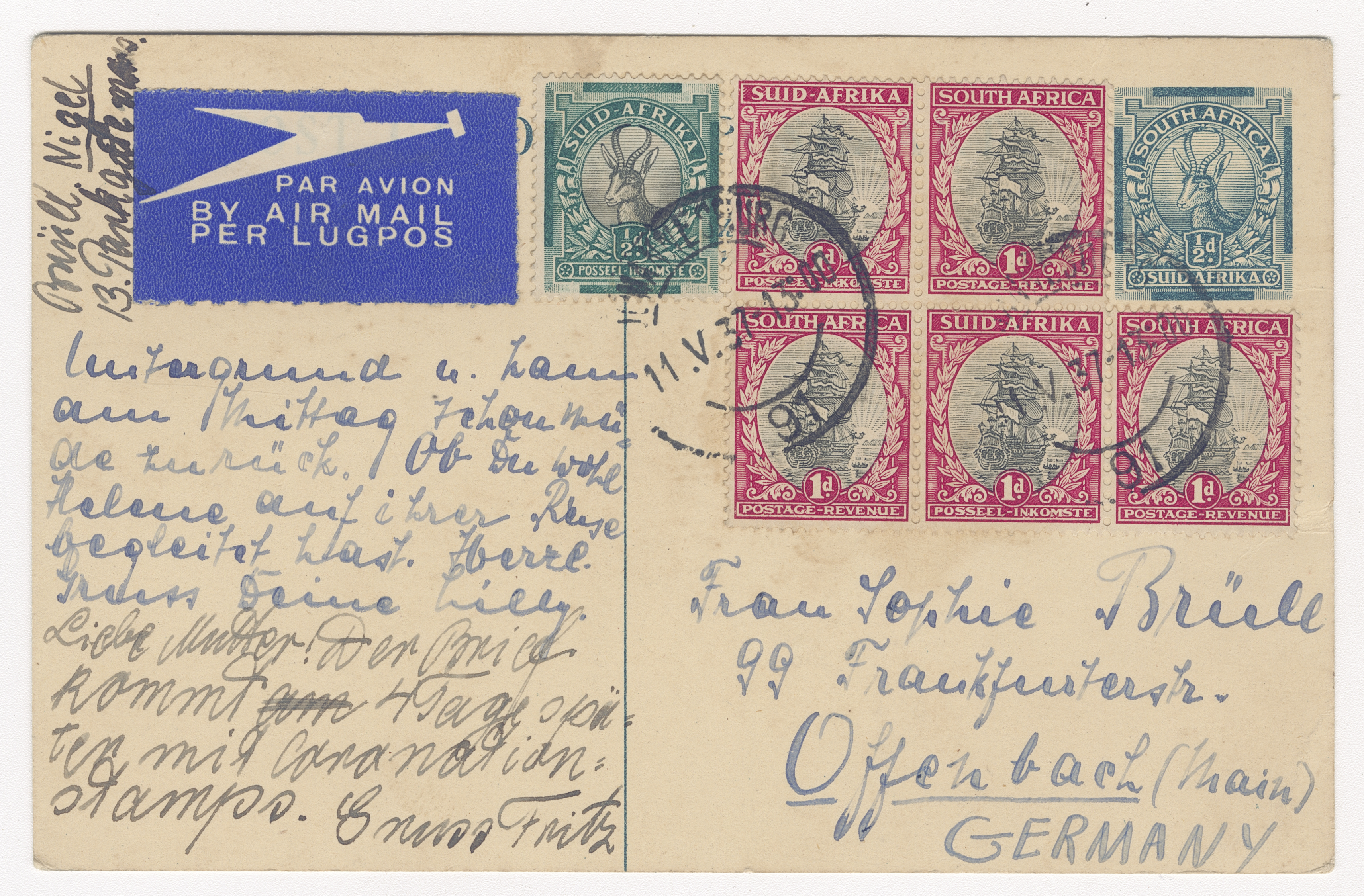

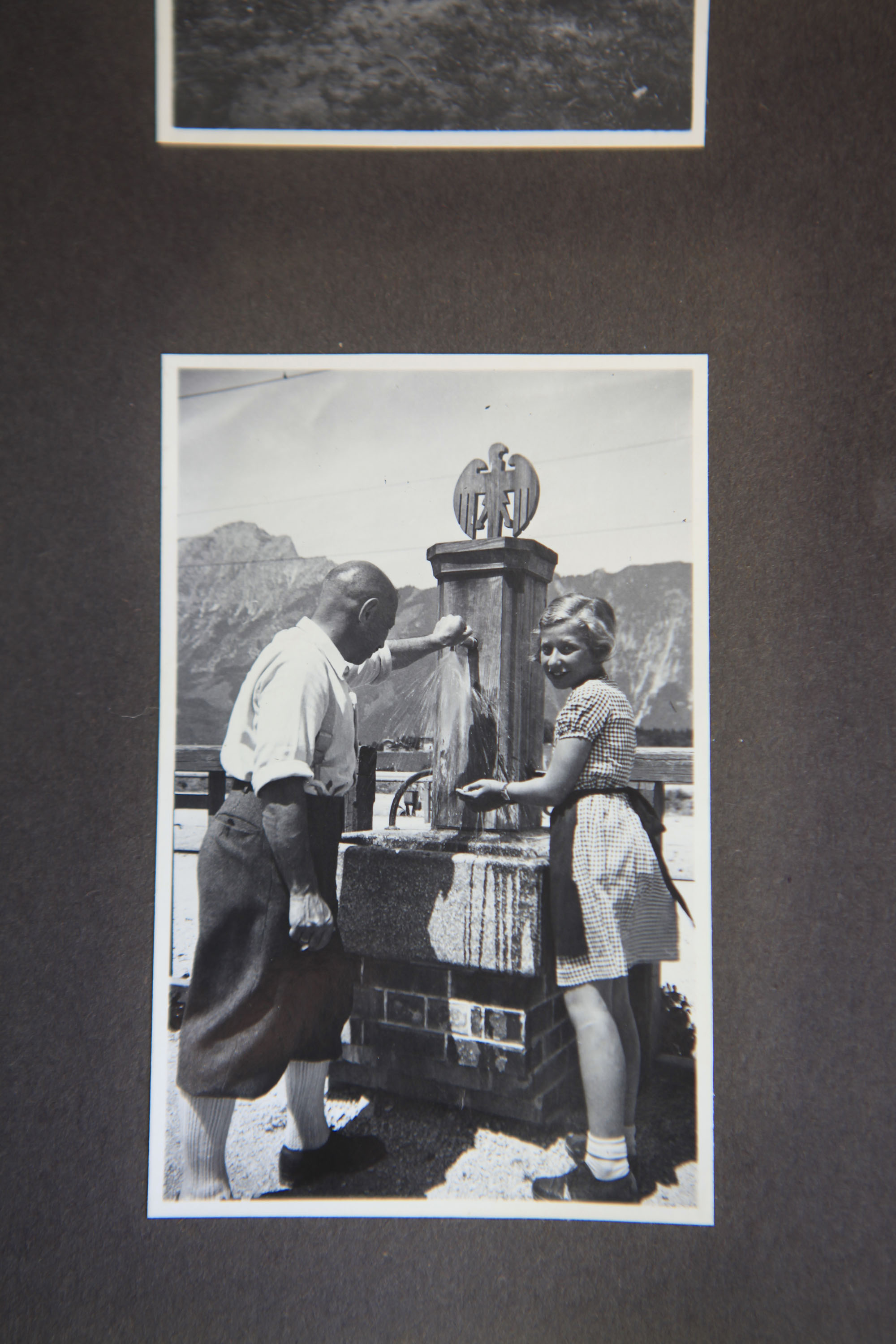

Over the last year myself and my father Gideon Mendel have become the custodians of a huge collection of documents, letters, objects and photographs. This collection traces our family history in Germany from the 18th Century through to the the Franco-Prussian war, the First World War, bourgeois life in the Weimar Republic, the Holocaust and life in apartheid-era South Africa. We have been working together to organise and make accessible this vast collection, each making our own separate creative responses.

Here is just a small collection of the vast array of images and documents we have available: